Why Canada can win the global AI race

“The doctors said it could be nothing, or it could be disaster.”

That’s how Brendan Frey recalls the moment that led him to realize artificial intelligence and genetics could work hand in hand. It was in 2002 and a gene test on the baby he and his wife were expecting had turned up an anomaly. Although the human genome had recently been sequenced, the doctors couldn’t say what, if anything, it meant. Making sense of life’s code would take years—there was simply too much data to work through.

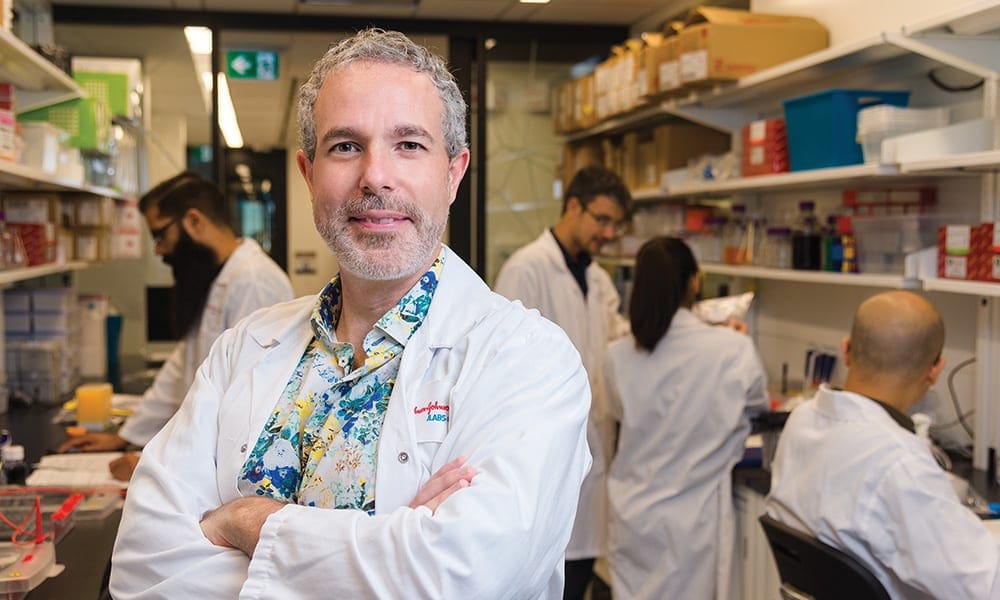

“As an engineer and a scientist, that was very frustrating to me,” says Frey. He turned to his expertise in AI—a field then so niche that it was borderline esoteric—and started building programs to crunch all that information.

Thirteen years later, after a series of major research breakthroughs, Frey founded Deep Genomics, now one of Canada’s more promising AI startups. The company uses AI to accelerate every aspect of drug development, from telling patients which mutation is causing their disease to getting regulatory approval for new therapies.

Deep Genomics works on the very limits of our scientific understanding. But it’s also on the leading edge of another phenomenon: a wave of AI innovation coming out of Canada. Says Frey, “There has never been a better time for entrepreneurs to build world-changing startups and scaleups in Canada.”

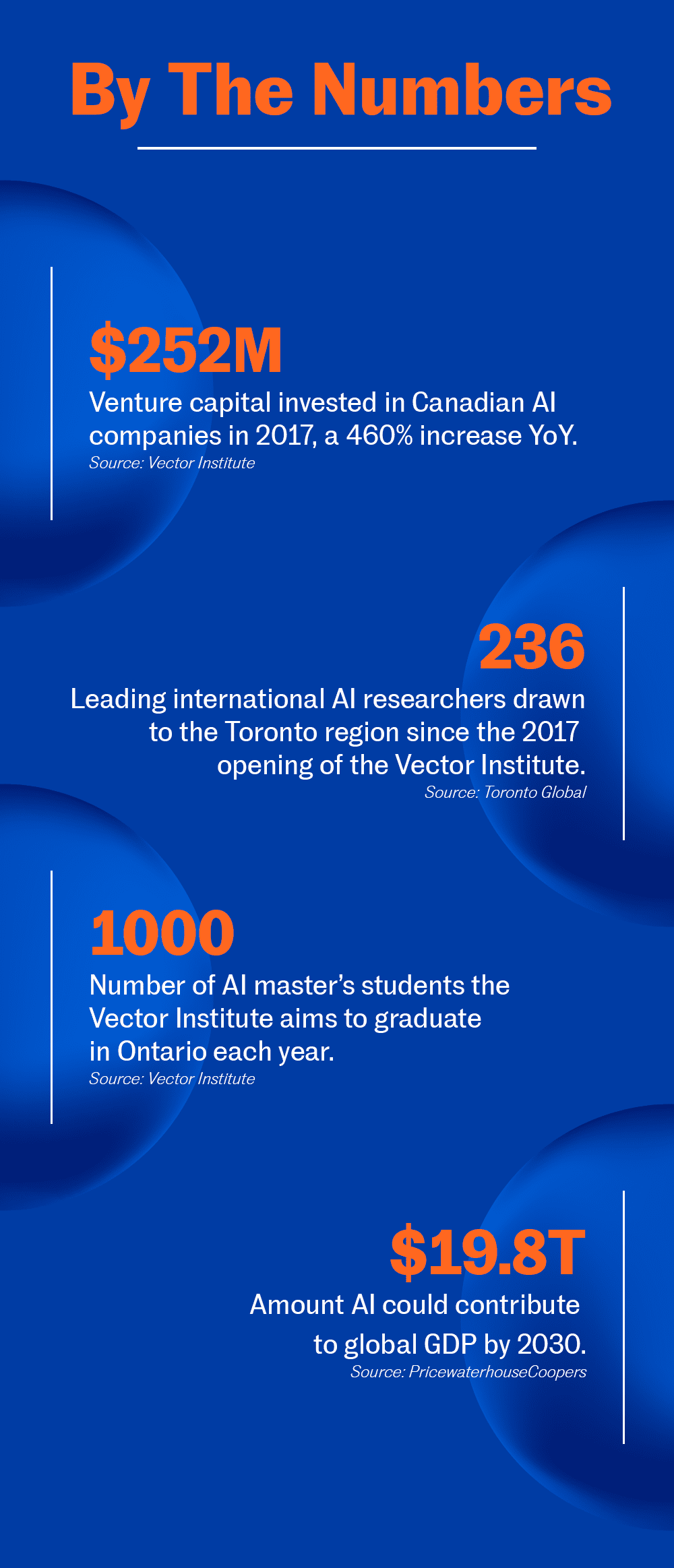

By some estimates, AI could add more than $15 trillion to the global economy in the next decade. A race is on to dominate the field, and the U.S., China and Europe are pouring funds into the effort.

But Canada was fastest out of the blocks—and is determined to hold on to its lead.

Two years ago, as news about artificial intelligence was making the leap from science journals to mainstream media, Canada’s government made a bold decision: If AI were the future, it should be shaped by Canadians. It became the first country in the world to rally around this new technology with a national plan to become one of its leaders.

Since then more than a billion dollars have been invested in the AI industry, with Toronto, Montreal and Edmonton emerging as internationally important centres for research and development.

Hardly a month goes by without an announcement of a major lab or office opening. Uber is developing self-driving vehicles in Toronto. Google Brain has opened hubs across Canada. DeepMind, whose software was famously the first to defeat a master of the complex board game Go, has opened an office in Edmonton. Microsoft is establishing a talent hub in Montreal. Samsung is expanding its machine-learning and robotic AI presence in Toronto and Montreal.

This astonishing growth is being fuelled by Canada’s deep reservoirs of talented computer scientists. By some estimates, the global population of skilled AI engineers numbers in the tens of thousands. Thanks to its relaxed immigration policies, Canada is attracting many to its shores.

Ed Clark, the former CEO of TD Bank who now chairs the Vector Institute for Artificial Intelligence, considers Canada perfectly placed to ride the AI wave: “It has great health systems, great education systems, good transportation systems and an immigration model that’s open to skilled people.”

Reihaneh Rabbany of the Montreal Institute for Learning Algorithms points out that Canada’s “welcoming reputation” has made it an attractive destination. The arrival of Collision, one of the world’s leading tech conferences, will bring 25,000 delegates to Toronto in May, and further solidify that reputation.

But there’s another reason Canada has so much expertise: It is, in many ways, AI’s spiritual home.

Much of the research underpinning current AI technologies was conducted in the labs of such superstar scientists as Geoffrey Hinton at the University of Toronto and Yoshua Bengio at the University of Montreal, who both worked on these ideas for decades before most others woke up to their potential. Much like Silicon Valley’s “PayPal mafia,” employees who went on to found or develop other big-name companies, Canada has a large cohort trained in its university labs who are now leading research efforts or building companies of their own.

Arms-length government agencies such as the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research also looked to the long term, investing as far back as the 1980s in what Elissa Strome, executive director of CIFAR’s Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy, calls “high-risk fundamental science.”

Focusing on basic science, says Strome, has equipped researchers to take a successful idea “to a place where it is now incredibly commercially viable.” Or, as Martha White, a fellow at the Alberta Machine Intelligence Institute (Amii) in Edmonton puts it, letting AI pioneers work on what “they thought was important” allowed them to flourish.

That helped Canada assemble one of the great concentrations of AI talent. The question now: What should the country do with it?

For people like Clark, the answer is simple: commercialize.

He points to other countries—China especially—now focused heavily on creating real-world applications for AI. “They’re saying, ‘You guys can win the theoretical side. We’re going to win the applied side.’ ”

That’s why Vector is dedicated to helping turn research into products. “We want to create as many applications for AI as we can,” he says.

Kerry Liu, co-founder and CEO of Rubikloud, which applies AI to the retail sector, goes further: “The only thing that matters here is commercialization.”

Canada’s lead is already being eroded, he says. “The misconception is that AI and machine learning is going to be a niche field, where you need to get a PhD to be successful. The reality is, every country in the world is going to teach this at the undergraduate level, maybe even high-school level.”

One challenge here is Canada’s small population; companies have fewer potential clients close to home. “If you’re in China, India, the U.S.,” says Ian Collins, CEO of Toronto’s Wysdom AI, “you might be mostly selling local. Canadians don’t have that option.”

So, Canadian companies have to think global right out of the gate. Wysdom, which produces AI-powered customer-service chat systems, has expanded to the U.S., Caribbean and is now focused on Europe.

Also critical, says Martha White, the Amii fellow and an assistant professor of computing science at the University of Alberta, is building bridges between academe and commerce: AI programs should include some business-related instruction to give students a better sense of how their work could be applied.

She also feels those trained in machine-learning should have career opportunities within traditional fields. “The routes for graduate students shouldn’t just be research or starting their own companies.”

But some caution against losing sight of how Canadians made their name.

“Having government funding that allows people to pursue these less popular, potentially more fundamental questions is very important,” says Angel Chang, an Amii associate faculty member relocating from Silicon Valley this year to Simon Fraser University in Vancouver. “That’s where Canada can have its advantage.”

It’s a compelling argument. By keeping a focus on where it’s strong while pursuing areas where it can shine, Canada can both stay competitive and make good use of what it has invested already.

“We’ve got everyone’s attention now,” Ed Clark points out. “There’s nothing wrong with us saying, ‘You know what? We’ve done well.’ Let’s shed that Canadian need to play down our successes. Because we’ve really got one here.”

Matt Gurney

Matt Gurney